Over the last quarter century, when the Bolivarian Revolution has been threatened, Beijing has provided economic support and offered political and diplomatic backing. With the presidential elections just days away, China is once again the ally on which the government relies.

The web of relationships and interests that shape the strategic relationship between Caracas and Beijing began to take shape in 1999, when the elected president Hugo Chávez proposed moving towards the construction of a multipolar world with alternative blocs to the “traditional” centers of power.

Guided by this premise, Chavez visited Beijing in 1999 and 2001, kicking off the China-Venezuela High-Level Joint Commission that elevated diplomatic relations to a Strategic Partnership for Shared Development. The scheme changed: from prioritizing agricultural and energy issues to strengthening political, economic, commercial and cultural ties.

In 2004, after winning a recall referendum, Chávez visited China to attract investments that would put him in an optimal position for his next battle: the 2006 elections. In addition to the agreed cooperation instruments, he created what later became the Chinese-Venezuelan Joint Fund (FCCV): a loan-for-oil scheme that allowed Caracas to cope with its difficulties in obtaining international financing.

The link was strengthened. The period 2006-2012 saw a massive flow of Chinese capital into Venezuela. Although the FCCV was the most relevant mechanism, investments in infrastructure and trade also increased. In 2010, a new financing fund was created through which the Chinese government transferred 20 billion dollars to Venezuelan coffers.

Venezuela’s dependence on China became evident when it became the regime’s key lender, in its quest to obtain monetary liquidity to maintain the Chavista social program. The loans compromised future oil production. The flow was enormous: 62 billion dollars. But it was not used to finance projects that offered a productive link. A lost opportunity.

The financing instrument was used primarily to help Chávez pave the way for his re-election – his fourth term – in the 2012 elections. Three million appliances, thousands of houses, hundreds of buses, private cars, mobile phones and laptops were purchased. These were campaign gifts that Chavismo handed out at subsidized prices. These were “Chinese gifts” that decisively influenced Chávez’s re-election.

Following Chavez’s death, the new leader of the ruling party, Nicolas Maduro, narrowly won the April 2013 elections over opposition leader Henrique Capriles. The opposition and its international allies did not accept the results, alleging irregularities in the vote count. The following months were very turbulent for Maduro, as his legitimacy of origin was questioned by many countries.

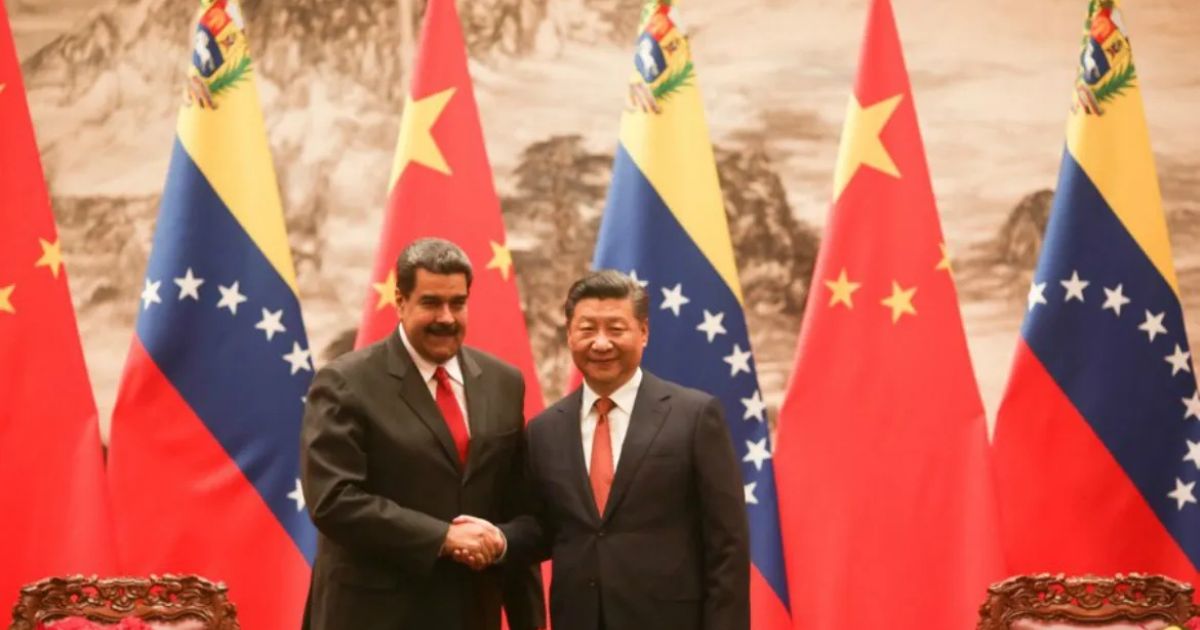

In this context, President Xi Jinping, newly elected, received within four months three key figures of the Venezuelan regime: Diosdado Cabello, president of the National Assembly; Vice President Jorge Arreaza; and the controversial president-elect, Nicolás Maduro. Shortly afterwards, Beijing elevated the bilateral relationship to a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership and renewed the FCCV, providing Maduro with another 14 billion. This economic aid remained unchanged until the crisis caused by the collapse of the national oil industry.

Despite the slowdown in financing and the internal crisis that the South American country was beginning to experience, Beijing continued to offer its political support to Caracas. In 2016, part of the bilateral debt was renegotiated, which gave Caracas oxygen before the US sanctions of 2017 and 2019 made the situation more difficult again.

In that scenario, China threw a new lifeline in the 2018 elections. Maduro was re-elected after upending democratic norms, amid accusations of fraud by the opposition. However, China was one of 14 countries to congratulate Maduro. In September of that same year, Xi received his Venezuelan counterpart and reiterated his desire to strengthen the bilateral relationship. And, when in 2019 the then president of the National Assembly, Juan Guaidó, declared himself interim president, Beijing continued to recognize Maduro, making use of its veto power in the UN Security Council to block a resolution that recognized Guaidó as the legitimate president of Venezuela.

Economically, China has maintained its support. It helped Caracas place its oil on the Chinese market when the US oil embargo was in force and, in the context of the pandemic, Beijing sent Venezuela 110 tons of medical supplies, one million PCR test kits, eight million masks and two million gloves, as well as vaccines and other donations.

Chinese support was reciprocated by Maduro in all areas. His administration supported all the sensitive causes of Chinese foreign policy: the “One China” principle, which recognises Taiwan as an inalienable part of China; the Hong Kong Security Law; territorial disputes in the South China Sea; or criticism of human rights abuses in Xinjiang and against the Uighur community. The relationship between the two thus responded to a mutual political calculation, based on the strategic interests of each party.

In the current presidential campaign, China has once again become a key player in Maduro’s bid to remain in power for another six years. During his visit to Beijing in 2023, the bilateral relationship was elevated to the rank of All-Weather Strategic Partnership. The cooperation model is thus incorporated into a new dynamic based on trade agreements in areas other than oil and giving prominence to subnational actors. With this new integration scheme, Caracas takes the Chinese development model as an example in the reforms it wants to carry out.

In an internal propaganda key, Maduro has promised to build power plants and other projects with Chinese capital, but he has also expressed his desire to formalize his full membership in the BRICS, the group of emerging countries dominated by China. And he boasts of Chinese support to guarantee his security in the event of a social conflict with the opposition. His alliance with China ensures that he has “cutting-edge technology, in drone combat and anti-drone (sic),” he said. A few days ago he threatened “a bloodbath and a civil war” if he and his party are removed from power.

The Asian power has kept its part of the deal. In March, when it was believed that Maduro would block the candidacy of the opposition party Plataforma Unitaria, Beijing did not hesitate to support the Venezuelan electoral system while demanding that the United States government “avoid interference” in Venezuelan affairs. In June, its Foreign Ministry spokesman questioned the “plundering” to which Venezuela was being subjected by the US due to the “seizure” of CITGO Corp, a subsidiary of PDVSA.

Paradoxically, while Chinese diplomacy frequently refers to the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of third countries, the unconditional political, diplomatic and economic support offered by Beijing has been key to keeping the Bolivarian regime in power. A regime contrary to the principles of representative liberal democracy and which extols the achievements of Chinese authoritarianism.

The inertia of this alliance is clearly visible. Both parties consider their relationship a strategic priority, especially Venezuela, which sees China as an ally in its struggle with the US. The link is strong in different areas, including economic, cultural and military, but it is fundamentally political. Therefore, Beijing has been key to the electoral victories of the ruling party, both for the economic aid to Chavez and for the support given to Maduro when his legitimacy was questioned.

Not only must the idea of a neutral China in Venezuelan affairs be refuted, but it seems clear that China prefers a Venezuela with Maduro in power, as this guarantees it an unconditional ally in the midst of a much larger and more important geopolitical dispute with the United States. This does not exclude, however, that Beijing could develop normal relations with a Venezuelan opposition government headed by Edmundo González Urrutia, a candidate who, according to most polls, has support of close to 60%. If the time comes, Beijing will face a dilemma: choose whether to continue supporting its preferred ally, or whether to open up to accepting a new stage in the bilateral relationship.

Carlos Piña is a political scientist and internationalist specialized in the relationship between China and Latin America and collaborator of the “Sinic Analysis” project in www.cadal.org