More than 700,000 migrants living illegally in California will have access to free health care starting Monday under one of the state’s most ambitious coverage expansions in a decade.

It is a measure that will cost the state about $3.1 billion per year and brings California closer to the Democratic goal of providing universal health care to its nearly 39 million residents.

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom and lawmakers agreed in 2022 to provide access to health care to all low-income adults, regardless of their immigration status, through the state’s Medicaid program, known as Medi-Cal.

California is the most populous state that guarantees this type of coverage, but not the first: Oregon began doing so in July.

When he proposed the changes two years ago, Newsom called the expansion “a transformative step toward strengthening the health care system for all Californians.”

Newsom pledged when the state had the largest budget surplus in its history. But by the time the program gets underway next week, California will face a record $68 billion deficit, raising questions and concerns about the economic implications of the expansion.

“Regardless of where you stand on this, it doesn’t make sense for us to continue increasing our deficit,” said Republican Sen. Roger Niello, vice chairman of the House Budget and Fiscal Review Committee.

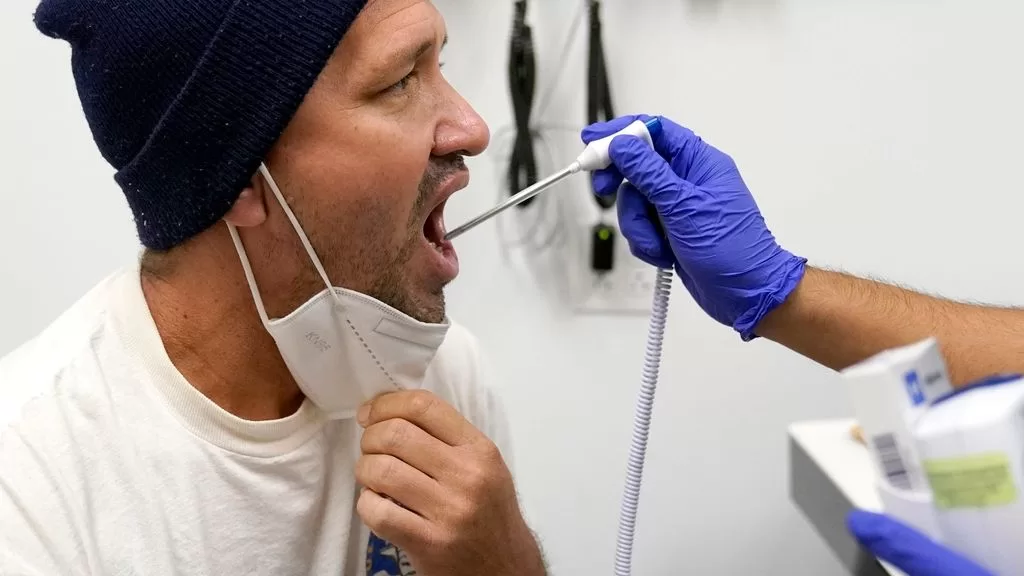

Immigration and health advocates, who spent more than a decade fighting for change, said expanding coverage will close a gap in access to health care and save the state money in the long run. Those who reside there illegally often delay or avoid going to the doctor because they cannot afford to finance the cost, which makes treating them more expensive when they finally go to the emergency room.

“It is a sure victory because it allows us to provide comprehensive care and we believe this will help keep our communities healthier,” said Dr. Efraín Talamantes, chief of operations at AltaMed in Los Angeles, the largest qualified health center in the state.

The update will be California’s largest health expansion since former President Barack Obama’s Affordable Care Act was implemented in 2014, allowing states to include adults below the federal poverty level in their Medicaid programs. . The percentage of uninsured people in California went from about 17% to 7%.

But a large part of the population was left out: adults living in the United States without proper permits, who cannot benefit from most public programs although many of them have jobs and pay taxes.

Some states have used their taxes to cover part of the health expenses of some low-income migrants. In 2015, California expanded coverage first to low-income children without legal status, and later to young adults and those over 50.

The last pending group — adults between 26 and 49 years old — will now be able to access the state Medicaid program.

The state doesn’t know exactly how many people will enroll through the expansion, but officials said more than 700,000 people will gain comprehensive health coverage that will allow them to access preventive care and other treatments. This is more than the entire Medicaid population in several states.

“We had that asterisk based on immigration status,” said Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access California, a consumer advocacy group. “Just from a numbers standpoint, this is a big deal.”

Republicans and other conservative groups are concerned that the new expansion will put more pressure on an already overwhelmed healthcare system and criticized the cost of the expansion.

State officials estimated the expansion will cost $1.2 billion in the first six months, and $3.1 billion annually thereafter. The Medi-Cal allocation, now about $37 billion annually, is the second largest in California’s budget, according to an analysis by the nonpartisan group Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Many migrants avoid accepting any public program or benefit for fear that, over time, this will prevent them from regularizing their situation based on the “public charge” law. Federal law requires those who want to become permanent residents or obtain legal status to prove that they will not be a burden, or “public charge,” to the United States. Under President Joe Biden’s administration, the rule no longer considers Medicaid as one of these factors, but the fear persists, said Sarah Dar, policy director at the California Immigrant Policy Center.