The hope that had driven her to travel thousands of miles from Guatemala in 2019, with her young son clutched to her chest, gave way to desperation and loneliness in Fort Morgan, a cattle town on the eastern plains of Colorado, where some residents They stared at her and the wind blew so hard that she once slammed open the doors of a hotel.

Simon, who was pregnant, tried to hide her desperation each morning when her young children asked about their father.

Confusing feelings in migrants

For millions of migrants who have crossed the southern border of the United States in recent years, and who have gotten off buses in places across the country, those feelings can be a constant companion. What Simon found in that modest town of just over 11,400 people, however, was a community that welcomed her, putting her in touch with legal advice, charities, schools and soon with friends, a unique support network built over generations. of immigrants.

In the small town, migrants carve out quiet lives, far from big cities like New York, Chicago and Denver that have struggled to house asylum seekers, and from the halls of Congress where their future is being negotiated.

Fort Morgan’s migrant community has become a blessing for newcomers, nearly all of whom end dangerous journeys to face new challenges: processing asylum claims; get a salary that covers food, a lawyer and a roof; enrolling their children in school and managing a language barrier, all under the threat of deportation.

The United Nations held up the town, 80 miles (129 kilometers) west of Denver, as an example of rural integration for refugees after a thousand Somalis arrived to work in meat processing plants in the late 2000s. 2022, grassroots groups sent migrants living in RVs to Congress to tell their stories.

Hundreds of migrants have arrived in the last year. More than 30 languages are spoken at Fort Morgan’s only high school, with translators for the most common and a telephone service for others. On Sundays you hear Spanish in the pulpits of six churches.

The demographic change of recent decades has forced the community to adapt. Local organizations hold monthly support group meetings, inform students and adults about their rights, teach others how to drive, make sure children go to school, and refer people to immigration attorneys.

Now, Simon herself tells her story to those getting off the buses. The population cannot eliminate the burden, but it can make it lighter.

“It’s not like at home, where you have your parents and your whole family around you,” Simon tells people he meets in grocery stores or in line to pick up their children from school. “If you have a problem, you have to find your own family.”

The task has grown as negotiations continue in Washington DC on an agreement that would tighten asylum protocols and reinforce surveillance at the border due to the immigration chaos with the entry of millions of undocumented immigrants seeking work and improving their living conditions.

On a recent Sunday, activist groups organized a posada, a Mexican celebration of the journey described in the Bible in which Joseph and Mary sought shelter for Mary to give birth and were turned away until they were offered a stable.

Before marching down the street singing an adapted song in which migrants seek shelter rather than Joseph and Mary, participants signed letters urging Colorado’s two Democratic senators and Republican Rep. Ken Buck to reject asylum rules. tougher.

A century ago, what brought German and Russian migration to the area was sugar beet production. Now, many migrants work in dairy plants.

In the 2000s there were several raids on businesses in the area. Friends disappeared from one day to the next, there were empty seats at school and gaps opened up in the lines at the factory.

“That really changed the understanding of how embedded migrants are in the community,” explained Jennifer Piper of the American Friends Service Committee, which organized the inn.

Guadalupe “Lupe” Lopez Chavez, who came to the United States alone from Guatemala in 1998 when she was 16, spends many hours working with migrants, including connecting Simon with a lawyer when her husband was detained.

On a recent Saturday, Lopez Chapez sat in the low-ceilinged office of One Morgan County, a nonprofit that has been helping migrants for nearly 20 years. In a folding chair, Maria Ramirez was searching through official envelopes dated November 2023, when she arrived in the United States.

Ramirez had fled central Mexico, where cartel violence claimed the life of his little brother, and was asking Lopez Chavez how he could get medical care. Ramirez’s four-year-old daughter — who danced behind her mother, blowing soap bubbles and popping ones that fell on her brown curls — has a respiratory problem.

Ramirez said he would work anywhere to move out of the living room where they slept, with just a blanket on the floor for a mattress.

In the office, which resembles a cozy common space in a hostel, Lopez Chavez recommended Ramirez consult with a lawyer before seeking medical attention. Sitting next to Ramirez were two settled migrants who offered him support and advice.

“A lot of what you heard in Mexico (about the United States) was that you couldn’t walk down the street, you had to live in the shadows, that you would be persecuted,” Ramirez said. “It’s beautiful to come to a community that is united.”

Lopez Chavez works with newly arrived migrants because she remembers being shackled after she was pulled over for a traffic violation in 2012 and handed over to U.S. immigration authorities.

“I just wanted to get out of there because I had never been caged before,” Lopez Chavez said in an interview as her eyes filled with tears.

At her first court hearing, Lopez Chavez and her husband were alone. In the second, after the community contacted her, she was surrounded by new friends. That wall of support allowed him to hold her head high as she fought her immigration case until she obtained a green card last year.

Now, Lopez Chavez works to sow that strength throughout the community.

“I don’t want any more families to go through what we go through,” said Lopez Chavez, who also encourages others to tell their stories. “Those examples give people the idea: ‘If they can handle their case and win, maybe I can too.’”

“Better treatment for new migrants”

In Fort Morgan, train tracks separate the trailer park, where many migrants live, and the city’s older homes. Some veteran migrants believe that new arrivals receive better treatment in the United States and feel that is not fair. The community cannot solve all the challenges and has not finished closing the differences between the different communities.

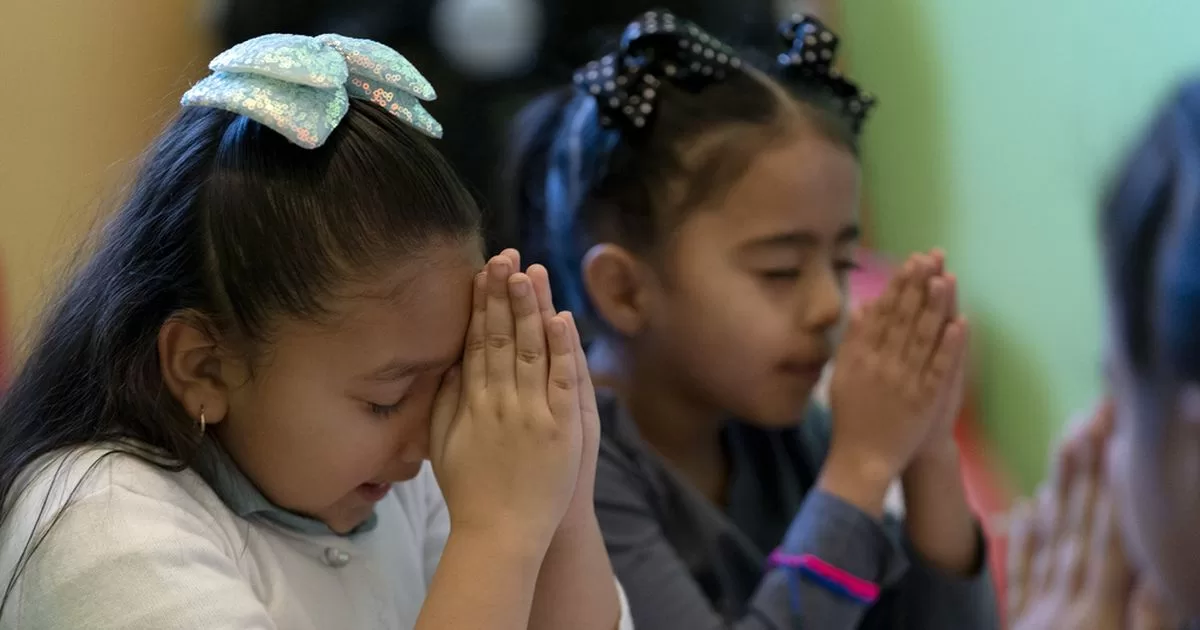

But at the posada, an event that drew a crowd to the One Morgan County offices, the tranquility of the community itself was visible on the faces of attendees as children in traditional costumes performed Mexican dances.

One of those who danced around the room was Francisco Mateo Simon, 7 years old. He does not remember the trip to the United States, but his mother, Magdalena, does.

She remembers how sick the little boy became as she carried him the last few miles to the border. Now, the boy lists facts about armadillos in his RV, and then points to his favorite ornament on his white plastic Christmas tree.

“That’s our new tree,” her mother said as her oldest daughter practiced English with a children’s book.

“It’s new,” he repeated. “It’s our first new tree because in the past we only had trees from the thrift store.”

Source: With information from AP