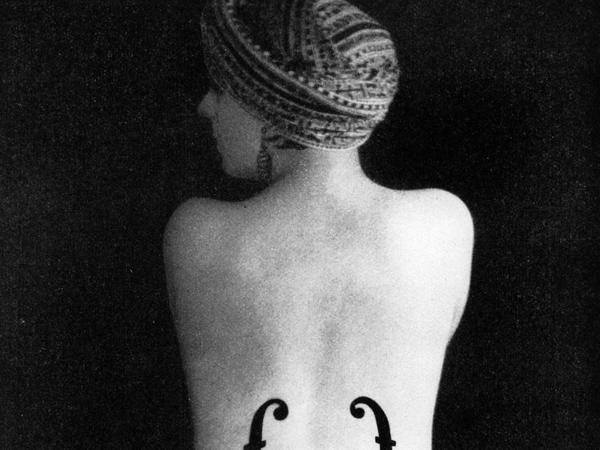

Little of her remains as an artist. Less than half an hour of music, a handful of paintings, an autobiography that has hardly been read – that’s about it. The fact that posterity still has a picture of her is due to a photo. It comes from her lover, a certain Emmanuel Radnitzky, and shows her naked back, tapering upwards in a sweeping curve, with the clou of two f-holes teasingly placed left and right of the spine, as if she were a musical instrument. Woman waiting to be played, a clear case of male fantasy. Or not?

The question runs through Mark Braude’s double biography of a couple who caused a stir and even more conversation in Paris in the 1920s. He is a somewhat coarse American, “half dock worker, half professor”, she a girl from the French provinces. He was fleeing his middle-class Jewish origins, she was facing the prospect of ending up as a seamstress in the nearest factory. When she began posing for him, it was the beginning of a relationship that turned their lives upside down. Emmanuel Radnitzky became the avant-garde artist Man Ray, Alice Prin danced under him nom ge guerre Kiki de Montparnasse on every table for a decade.

Braude outlines the background of this astonishing parallel transformation: the discrediting of traditions by the First World War, the longing for a radical new beginning, the upheaval in the arts and everyday life. Epatez le Bourgeois! Tact and restraint were suddenly considered yesterday’s, now it was about celebrating the moment with all the opportunities that presented itself. The most dazzling example of this: the picturesque, ragged artists’ village of Montparnasse on the left bank of the Seine, back then the place to be but this book isn’t about another bohemian moral harrassment. Braude is interested in the biographical model case.

Production community instead of a relationship of dependency

It is the relationship between artist and “muse” that is at stake here. If the whole world falls out of character, art and life flow into one another, why not speak of a production community instead of a relationship of dependency? The idea remains speculative by necessity – no one was present in the studio where Man Ray and the bold Kiki shared the bed and table – but it has a lot to offer.

She didn’t fit the image of a classic muse at all, drank, smoked, painted, wrote, as one of those new women who populated the big cities in the 1920s, and with her rough chansons she brought whole pubs to the boil. But he was no longer a painter prince of the old school, but primarily a photographer and as such relied on cooperation.

In this light, his/her best-known picture, the nude from the back, which has become a poster motif under the title “Le violon d’Ingres”, loses its clarity. Sure, it’s her body that’s on display, but does that make her seem passive? When you look over your shoulder, can’t you even guess a wink? Was she perhaps the secret conductor in the end? Braude, who has already appeared with a Napoleon monograph, interprets the pose against convention as an ironic vis-a-vis, a jointly staged game with expectations and habits in which she takes on the performative role and he sets the framework. A kiss of the muse with a silver gaze, so to speak.

One of the strengths of his colorfully told, pleasingly multi-layered biographical study is that the counter-examples are not concealed either: jealousies, bickering, turf wars in the Kiki Man Ray household.

The author saves his protagonists from the fate of appearing as mere theorists, instead showing them where they flouted conventions, as children of a time marked by contradictions.

A romantic soul often showed itself under the aplomb with which she appeared, and a commercial macho under his forced avant-garde gestures. “Dear, what is that, you silly? We don’t love, we fuck,” he told her during an argument. The apparent misogyny in it is then less a question of perspective.

At the same time, the book can be read as a contribution to current debates: Even in today’s popular, no longer so beautiful arts, it often remains unclear where male expectations are met and where female self-empowerment begins. Incidentally, “Le violon d’Ingres” recently fetched a record price of 12.4 million dollars at Christie’s, the highest amount ever paid for a photograph. Irony of success: Even if the rebellious Kiki from Montparnasse had had descendants, they would have gotten nothing from the deal. The right to the picture remains with the patriarchy for the time being.