On May 9, 1882, the engraver and graphic artist Georg Meisenbach received a patent for the process he called autotype (Greek: self-writing), which decisively improved the printing technique for photos and illustrations and was decisive for image representations in printed works up to the digital revolution.

In this type of letterpress printing, a raster negative is copied onto a metal plate coated with a photosensitive layer and then etched. Together with the architect Joseph von Schmaedel, Meisenbach founded the Autotype Company in Munich. Von Schmaedel contributed to Meisenbach’s invention with a marking machine that scored the grid lines with precision diamonds.

Georg Meisenbach (born May 27, 1841 in Nuremberg; † September 24, 1912 in Emmering) in a depiction from around 1905. He is regarded as the inventor of glass engraving grids and autotype.

The halftone template with autotype quickly replaced the practice of converting photos into woodblock prints. What Georg Meisenbach wanted to achieve with numerous experiments was also shaped by the spirit of reducing manual work. Although young photography was already producing high-resolution negatives and prints from them, there was no way of automatically including them in book and newspaper production.

In this section, we present amazing, impressive, informative and funny figures from the fields of IT, science, art, business, politics and of course mathematics every Tuesday.

The intermediate step employed a master woodblock printmaker and took time. The raster etching of halftone originals with 36, later 43 lines per centimeter, patented in 1882 as DRP 22244, replaced this intermediate step.

Statuette as the first autotype image in a newspaper

The first illustration with Meisenbach’s process is the depiction of a statuette in the Leipzig “Illustrirten Zeitung” of March 10, 1883 Honorary gift to the 2nd Bavarian Crown Prince Infantry Regiment. Responsible for this was von Schmaedel, who had been wounded in the Franco-Prussian War as a Bavarian officer in the regiment. Elsewhere, too, the military was in the foreground: in England, Henry Fox Talbot researched the halftone technique on which Georg Meisenbach based himself.

There or in the Canadian provinces, the British governor Prince Arthur appeared on the front page of a newspaper on October 30, 1869 in a technique that Leggotype called. Queen Victoria, who was in office at the time, is said to have been upset that she, as head of the Commonwealth, was not in the know.

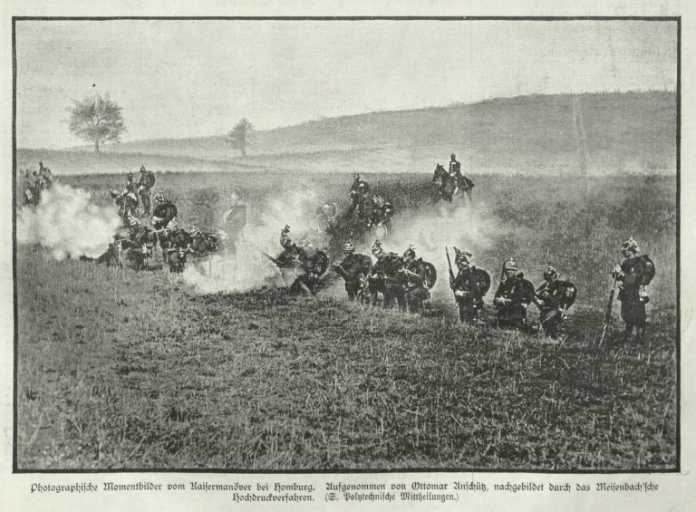

Ottomar Anschütz: Photographic snapshots of the Kaiser maneuvers near Homburg

(Image: Illustrirte Zeitung (Leipzig), March 15, 1884, no. 2124, p. 225)

Pioneering photographic developments through autotype

Two photographers were responsible for the further dissemination of the photograph in press reporting: In Germany Ottomar Anschütz with his pictures with “flash exposures” from military exercises, in which he experimented with short exposure times, in Austria David Ludwig, an officer who, like Anschütz, constructed cameras himself. In both cases, the military was very interested in the recordings, but so was science: in 1884, the Prague philosopher and physics professor Ernst Mach published a picture of a shotgun ball in flight in the Austrian “Photographic Correspondence”.

This had consequences a little later. Because Mach succeeded in 1888 with the help of August Toepler’s Schlieren photography proofthat a compression cone forms in front of the sphere and a tail cone forms behind it. This began research into gas dynamics and the measurement of velocity based on the speed of sound. In the meantime, Meisenbach’s first teaching institute for printing technology, the state “KK Teaching and Research Institute for Photography and Reproduction Processes” founded in 1888, developed from the “Photographic Correspondence”.

The Schlieren effect is still used by NASA today – here is a photo of a jet aircraft performing supersonic tests.

(Image: NASA)

Application also in pseudo-criminalistics

The photographic halftone technique had another notable user. In Britain, the eugenicist shared Francis Galton from 1878, for face shots, the imaging field in front of a camera in front of a shot in a small grid, so that the heads could be positioned exactly. Then he left condemned people photographed and proceeded strictly proportionally: if eight convicted murderers were to be photographed and the image plate permitted an exposure time of eighty seconds, each person was strictly aligned with the grid lines and photographed for ten seconds each. The superimposed photos of all those involved were intended to determine the type of murderer who “should have a similarity to everyone, but none of them more like one”, describe Lorraine Daston and Peter Galiston in their book “Objectivity” this hour of birth of biometrics and facial recognition. At the end of this process, of course, there was a woodcut master who was supposed to once again “scientifically” summarize the result that was photographed together. The types of images of criminals produced in this way proved to be completely useless in everyday police work when it came to discovering “typical murderers”.

However, the autotype proved useful for explaining how the human eye works. In the influential work “The Life of Man” by the gynecologist Fritz Kahn, the illustrator Roman Rechn drew in 1923 exactly how the grid in the eye fundus of the retina like an autotype (PDF file, page 10) works. When computers got down to raster technology and images were digitized, there were funny results. Digitized with great effort (allegedly several Calcomp plotters were worn out). Philip Paterson in 1964 the Mona Lisa from “Len de Vinci” based on the line/contone technique on a CDC supercomputer and called it Digital Mona Lisa.

The hackers at MIT then made fun of this and produced ASCII-Art titled on a PDP-8 “Lizzy of the Lineprinter (p. 14). With the advent of phototypesetting and later DTP and digital printing, along with lead typesetters, autotype largely disappeared from everyday printing.

(beautiful)