Once nearly impenetrable for migrants heading north from Latin America, the jungle between Colombia and Panama this year became a fast but dangerous route for hundreds of thousands of people from around the world.

Motivated by economic crises, government repression and violence, migrants from China to Haiti decide to risk spending three days in deep mud, rushing rivers and bandits. Enterprising locals offered guides and porters, set up camps and sold supplies to migrants, using color-coded bracelets to keep track of who had paid for what.

Enabled by social media and Colombian organized crime, more than 506,000 migrants—nearly two-thirds Venezuelan—had crossed the Darien jungle by mid-December, double the record-setting 248,000 last year. Before that, the record was just 30,000 in 2016.

Dana Graber Ladek, Mexico director of the United Nations International Organization for Migration, said migration flows through the region this year were “historic numbers that we have never seen before.”

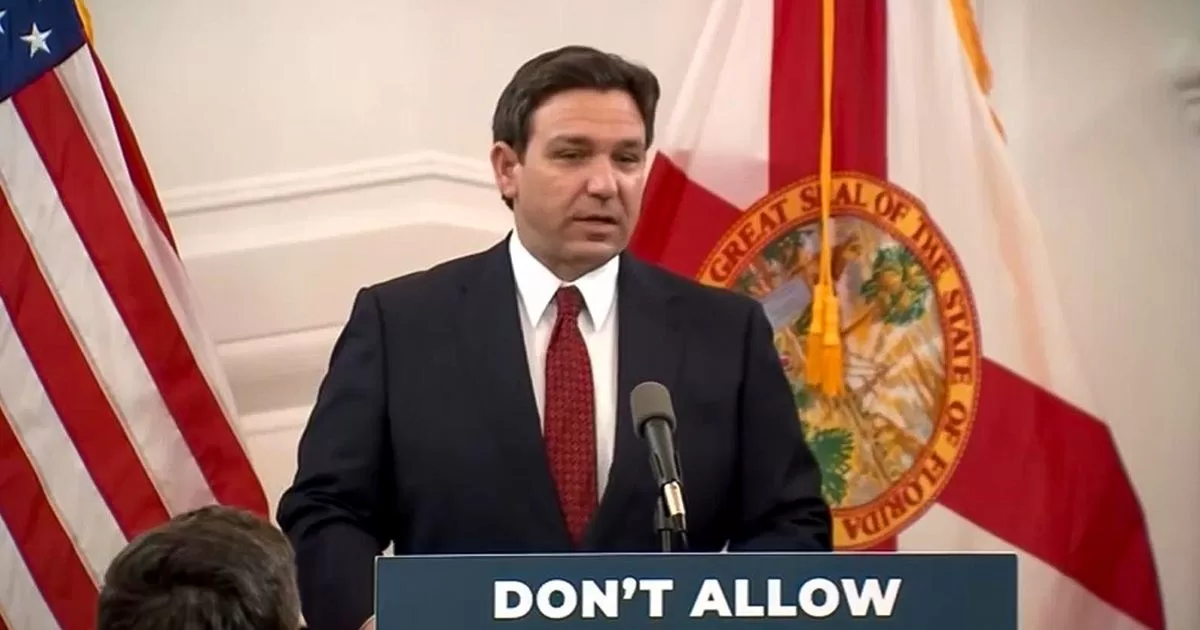

In Washington, the debate has shifted from efforts earlier this year to open new legal avenues to measures to keep migrants out as Republicans try to build on President Joe Biden’s administration’s effort to get more aid to Ukraine to reinforce the southern border of the United States.

The United States began the year by opening limited slots to Venezuelans — as well as Cubans, Nicaraguans and Haitians — in January to enter legally for two years with a sponsor, while expelling those who did not qualify to Mexico. Their numbers dwindled somewhat for a time before rising again with renewed vigor.

Venezuelan Alexander Mercado had only been back in his country for a month after losing his job in Peru when he and his partner decided to leave for the United States with their young son.

Venezuela’s minimum wage was then equivalent to about $4 a month, while 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds) of beef cost about $5, said Angelis Flores, his 28-year-old wife.

“Imagine how someone survives on a salary of $4 a month,” she said.

Mercado, 27, and Flores were already on their way when in September the United States announced that it would grant temporary legal status to more than 470,000 Venezuelans already in the country. Weeks later, the Biden administration said it would resume deportation flights to the South American nation.

Mercado and Flores walked the well-traveled trail through the jungle for three days. Flores and her son, in particular, became seriously ill. She believes they became infected from the contaminated water they drank along the way.

Flores remembers that there was a body in the middle of the river and that black birds were eating it.

For Mercado and Flores, the journey sped up once they left the jungle. In October, Panama and Costa Rica announced an agreement to accelerate the passage of migrants through their countries. Panama transported them by bus to a center in Costa Rica where they were held until they could buy a bus ticket to Nicaragua.

Nicaragua also seemed to choose to accelerate the passage of migrants through its territory. Mercado said they crossed in buses in one day.

After discovering that Nicaragua had lax visa requirements, Cubans and Haitians arrived in that country on charter flights with round-trip tickets that they never intended to use. Citizens of African countries took several connecting flights through Africa, Europe and Latin America to reach Managua and begin traveling by land to the United States, and thus avoid the Darien region.

In Honduras, Mercado and Flores received a pass from the authorities that gave them five days to cross the country.

Adam Isacson, an analyst who tracks migration at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), said Panama, Costa Rica and Honduras grant migrants legal status while they transit through those countries, which have limited resources; and by allowing migrants to pass legally, they make them less vulnerable to extortion by authorities and human smugglers.

Then there are Guatemala and Mexico, which Isacson called the “‘let’s make it look like we’re blocking you’ countries,” as they try to score points with the U.S. government.

For many, that has meant spending money to hire smugglers to cross Guatemala and Mexico, or exposing themselves to repeated extortion attempts.

Mercado didn’t hire a human smuggler and pay the price. It was “very difficult to get through Guatemala,” he said. “The police kept taking money from us.”

But that was just a taste of what was to come.

One recent afternoon, standing outside a shelter in Mexico City with her son, Flores recounted all the countries they had passed through.

“But they don’t rob you as much, nor extort you as much, nor return you as much as when you arrive here in Mexico,” he said. “This is where the real nightmare begins, because as soon as you enter they start taking a lot of your money.”

The Mexican immigration system was thrown into chaos on March 27, when immigrants detained at a detention center in the border city of Juárez, across from El Paso, Texas, set fire to mattresses inside their cell in apparent protest. The highly flammable foam from the mattresses filled the cell with thick smoke in an instant. The guards did not open the cell and 40 immigrants died.

The head of the immigration agency is among several officials charged with crimes ranging from negligence to homicide. The agency closed 33 of its smaller detention centers while it conducted a review.

Unable to hold many migrants, Mexico moved them around the country using brief, repeated detentions, each an opportunity for extortion, said Gretchen Kuhner, director of the Institute for Women in Migration (IMUMI). a non-governmental legal services organization. Proponents called it the “attrition policy.”

Mercado and Flores arrived as far as Matamoros, across the border from Brownsville, Texas, where they were detained, held overnight at an immigration center in the border city of Reynosa, and then flown the next morning 1,046 kilometers (1,046 kilometers). 650 miles) south to Villahermosa.

There they were released, but without their cell phones, shoelaces or money. Mercado had to wait for his brother to send them $100 so they could try to return to Mexico City via an indirect route that forced them to travel by truck, motorcycle, and even on horseback.

At the end of November, they had just returned to Mexico City again. This time Mercado was determined: they will not leave Mexico’s capital until the United States government grants them an appointment to request asylum at a border port of entry.