He also took advantage of the people’s discontent to promote his “revolution”, put the international community in check and led a group of armed leaders as dangerous as those of today.

That’s why everyone is wondering, inside and outside Haiti, if Guy Philippe is back to his old ways.

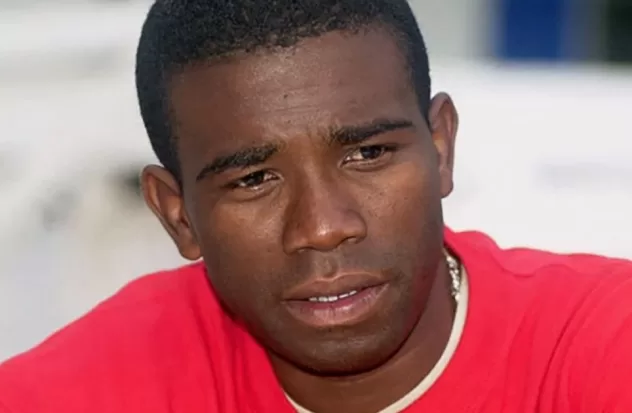

“Philippe is coming to play a negative role at the moment; “It is a step forward in all this chaos that already exists in the country,” political analyst Camille Chalmers told DIARIO LAS AMÉRICAS, about this former police commissioner who in 2004 led an uprising against then-president Jean Bertrand Aristide, who later launched him. to politics before his capture by DEA agents in July 2017.

Guy Philippe, now 56 years old, returned to Haiti on November 30, 2023, deported from the United States where he served a six-year sentence for conspiracy linked to drug trafficking and money laundering. Released by the police, he was received the next day as a hero in his native enclave in the department of Grand’Anse (southwest).

Since then he began to tour the country, first through nearby towns in the south, then through the north, where he defined his objectives: “This revolution it will be for you; “We must believe in this revolution, it cannot be done without us!” the former officer harangued in Ouanaminthe, guarded by very well-armed agents of the Protected Areas Security Brigade (BSAP), a police unit that for many has become his praetorian guard.

In search of power

Philippe’s fiery speech, which in that town in the northeast of the country demanded that Prime Minister Ariel Henry resign before he himself dismisses him, is seen by many as something that should be taken into account, especially if he is interested in seeking power. .

“It’s possible so,” Chalmers said via video call. “Philippe, who even spoke of declaring a general amnesty for gangs, will probably seek to form alliances to achieve his goals, either with him at the helm or supporting someone else.”

That’s how it has been. After his explosive appearances at the beginning of the year, the former officer remained low profile until Henry’s announcement that he would resign as soon as a presidential council created by the main actors in Haitian society at the request of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) is installed. , a proposal that Philippe rejected.

His party, Réveil National, proposed at the beginning of March the formation of a council with the former commissioner at the head, a formula that the main opposition leader, Jean-Charles Moïse, of Pitit Dessalines, decided to support with some changes, making these former rivals into allies against the government.

But in an unexpected turn this Wednesday, March 20, Moïse, who had rejected CARICOM’s call to join the council, presented his representative to that body, (allegedly induced by foreign diplomats) effectively breaking the brief alliance with the former coup leader. .

“The announcement of Henry’s resignation was quietly seen as a relief by some US and regional officials, but it also created new challenges as the region attempts to cobble together a temporary governance structure from afar to lift Haiti out of its crisis,” he wrote. This week in Foreign Policy, Robbie Gramer, expert analyst in diplomacy and national security.

One of those challenges is to implement the solution proposed by CARICOM, which faces the laxity, tricks and suspicions of Haitian politicians: two sectors of them changed their representatives in the council, one could not agree until the end of the deadline and another joined the project when he had initially rejected it.

The Presidential Council must appoint a prime minister and with him propose a provisional electoral council that calls for elections. When the first is officially formed, CARICOM must send it to Henry, who is still at the head of the government, for its endorsement and publication in the official gazette. The Monitor.

The other challenge is the lack of clarity regarding who could succeed the government in a country where — according to Chalmers — the opposition has been dispersed since 2010 as a result of the actions of the extreme right and the alliances between the assassinated president Jovenel Moïse and Henry and the social democrats.

The place has been occupied by gang members like Jimmy Chérizier (Barbicue), who presents himself as a defender of the popular class, and the former police officer (now with a new image) who in 2006 already ran for president with meager results ( he barely achieved 1.92% of the votes), and which improved in 2016 when he was elected senator for Grand’Anse.

“Philippe’s interest would be linked to the messianic perception he has of himself, and to achieve that goal he could take advantage of his old connections and mitigate the impact of gang violence through institutional means by assuming the role of mediator,” he commented in December to the InSight Foundation, professor at the University of Virginia, Robert Fatton.

Another specialist in Haitian affairs, Jake Johnston, of the Washington-based Center for Economic and Policy Research, told The New York Times on the same day of the former commissioner’s arrival in Haiti that, “given his history, his old ties and his political ambitions, it can be expected that he will have some influence on the current political situation in the country.”

Who is Philippe?

Guy Philippe was born on February 29, 1968 in Pestèl, a small fishing village in southwestern Haiti. His father, who was mayor of the town, was early concerned about his education, enrolling him with the Pauline fathers, first, in Jérémie, capital of the department of Grand’Anse, and then in one of the most renowned schools in the country, St. Louis. Gonzaga, in Port-au-Prince.

Between the late eighties and early nineties Philippe lived for a time in Miami. He then studied medicine for a year in Puebla, Mexico; He returned to Haiti to enlist in the Armed Forces and finally joined as a cadet, at age 25, at the General Alberto Enríquez Gallo Police Superior School, in Quito, Ecuador, where he studied between September 1992 and August 1995. .

Years later, the former coup leader confessed to having allowed Colombian cartels to use Haiti to send drugs to the United States between 1999 and 2003, when he was commissioner of the city of Cap-Haïtien, in operations from which he obtained income of 3.5 million dollars. He also transferred money between Haiti, Ecuador and the US, to his accounts, his wife’s and false accounts more than half a million dollars and bought a house in Florida.

“Everyone knows that he is linked to drug trafficking and mafias, that he has a past of criminal actions such as those that occurred between 2003 and 2004,” Chalmers told DIARIO LAS AMÉRICAS, recalling the accusations of human rights violations allegedly committed by Philippe and his men in the years when, in the midst of a serious crisis, He led the armed rebellion that led to the fall of Aristide and a new foreign intervention.

A crisis like the one happening now

While politicians resolve the future of the country outside it, the dangerous gangs have expanded their range of action and this week they penetrated one of the most exclusive neighborhoods of the Haitian capital: Petion-Ville.

The result of this new offensive, attributed to the “Kraze Baryè” gang, led by Vitelhomme Innocent, has been around two dozen bodies found in the streets of the commune, the murder of several local residents, kidnappings, damage to property and the daring attack on the headquarters of the Bank of the Republic of Haiti (Central Bank) that left four attackers dead.

During the last week, the United States sent marines to protect the American Embassy in Port-au-Prince and dozens of Americans left Haiti, as did hundreds of foreigners, including civilians and diplomatic personnel.

In the midst of this chaotic situation, hundreds of people also participated in a march in the capital asking that Philippe assume the presidency of the country, and supporting his “revolution”, the one that he has preached since he returned to Haiti and that one Sunday in January he turned into mandate: “The time for civil disobedience has come.”

—

Javier Valdivia

Especial

The author is a journalist, regional vice president for Haiti of the Committee on Freedom of the Press and Information of the Inter-American Press Association (IAPA), columnist in the Listín Diario newspaper of the Dominican Republic and collaborator of several media in Latin America and the United States. He currently resides in Miami.