Visibly pale and in poor health, the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan (69), has to survive the crucial, hot phase of the election campaign. Nevertheless, he appears more resolute than ever. For two decades, since March 2003, Erdogan has determined Turkey’s fortunes. He never had to fear for his power more than now.

Having recovered from a gastrointestinal illness, he recently drove to the Teknofest Air Show in Istanbul in Turkey’s first electric car, a Togg T10X. There he also used the photo opportunity with the selected astronauts for the first Turkish space mission. The two, Alper Gezeravcı and Tuva Cihangir Atasever, will fly to the International Space Station (ISS) for a fortnight.

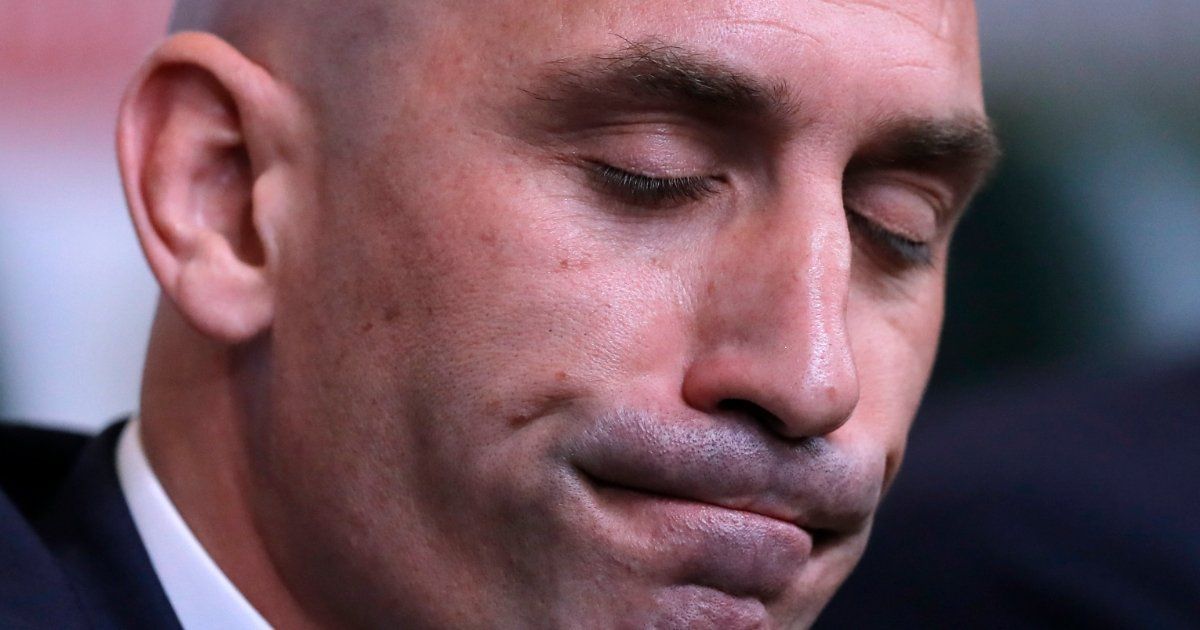

Erdogan vs. Kilicdaroglu: A head-to-head race

On May 14, the Turks will elect a new president and a new parliament. Most current polls predict a head-to-head race, with Erdogan ahead of his opponent in the first round, but losing to the Social Democrat Kemal Kilicdaroglu (74) in a possible runoff. Given the statistical errors in polls, anything seems possible, including a victory for one of the rivals in the first ballot.

Almost 60.7 million voters live in Turkey. In addition, there are around 3.4 million voters abroad who were able to register with the High Electoral Committee and thus vote from abroad. There are no postal voting options. In Germany there are almost 1.4 to 1.5 million people entitled to vote.

They have been voting since April 27 and were able to cast their votes in Turkey’s consulates general on May 9. There were also polling stations like in Aachen, where there is no consulate, but voting was possible from April 29th to May 1st. Turks from the neighboring Netherlands and Belgium also voted in Aachen.

Erdogan often receives more votes abroad

In previous elections, participation in Germany was around 50 percent, with Erdogan getting more votes than at home. This time, numerous members of the opposition are mobilizing who want to contribute to the fall of Erdogan from Germany. A higher turnout is expected.

The six-party alliance led by Kilicdaroglu of the social-democratic, Kemalist CHP (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi) is backed by the nationalist İyi Parti of ex-MHP Meral Akşener.

The far-right MHP (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi), under Akşener’s former rival for party leadership Devlet Bahçeli, is behind Erdogan. With the Demokrasi ve Atılım Partisi (Deva) under Ali Babacan, a split from Erdogan’s AKP party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi) belongs to the Kilicdaroglu camp.

They also include former Erdogan comrade-in-arms Ahmet Davutoğlu with his Gelecek Partisi (GP), the liberal-conservative Demokrat Parti (DP) and the Islamist Saadet Partisi.

In addition to the MHP, Erdogan can also count on the Büyük Birlik Partisi (BBP), classified as right-wing extremist, and the Islamist Yenid Refah Partisi (YRP), which in turn is a splinter group of the Saadet Partisi.

The Kurds as an election campaign issue

The incumbent president takes every opportunity to campaign. Due to illness, he was unable to attend the inauguration of the Akkuyu nuclear power plant. He allowed himself to be connected via video transmission, but that did not work at the previously announced time either, which is why the inauguration ceremonies had to wait for Erdogan. Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was also connected via video, had also been waiting and waved happily to his counterpart with best wishes for a speedy recovery.

The air show also served as a backdrop for an election campaign appearance. Erdogan complained that his rival in the presidential elections, Kilicdaroglu, had transformed Atatürk’s party into a “western club hostile to the Turks”. Turkey’s enemies would gather behind Kilicdaroglu, he denounced and accused Kilicdaroglu of being close to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is banned in Germany.

Erdogan’s party deputy in the AKP, Binal Yilderim, recently claimed that the “Seven Party Coalition” plans to pardon the PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan, who has been sentenced to life imprisonment for terrorism, and to legitimize the PKK and the Gülen movement.

Last week, the pro-Kurdish HDP (Halkların Demokratie Partisi) called on its supporters to vote for the joint candidate from six other opposition parties, Kilicdaroglu.

Yilderim derives his allegations from this and from a statement by Kilicdaroglu about the YPG, the military wing of the Kurdish-Syrian Democratic Union Party (PYD), which, unlike Erdogan, does not regard Kilicdaroglu as a terrorist organization.

Erdogan can be celebrated in monumental campaign spots

Erdogan’s election campaign, whose image suffered greatly from the fatal consequences of corruption during the devastating earthquake in February, is aimed at massively disavowing Kilicdaroglu. It’s a tried-and-tested strategy that Akşener also faced in past elections. She recently complained that the press close to Erdogan accused her of having extramarital affairs, thereby harming her family.

Akşener went on the offensive in mid-April. Her family belonged to the Muslim minority from the Greek drama, she let the public know and acknowledged her own past as a refugee.

Kilicdaroglu declared that he was an Alevi. This is rather unsuitable for catching votes in the 896 Ditib communities in Germany. Between 15 and 20 percent of Turks belong to the second largest religious community in Turkey. They don’t live by the five pillars of Islam. Women and men are equal, the pilgrimage to Mecca is omitted, as is Ramadan. Unlike the Sunni mosques, their places of prayer and gathering, the so-called cemevis, are not financed by the state but privately.

As a contrast to Kilicdaroglu, the self-confessed, devout Sunni Erdogan can be celebrated in monumental campaign spots as the one who turned the world heritage site, the former Byzantine cathedral Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, which had become a museum under Kemal Atatürk, back into a mosque.

Unity on hatred of Syrian refugees

The electoral alliances of Erdogan and Kilicdaroglu are unanimous in their attitude towards the Syrian war refugees. They want to expel them as soon as possible after the elections, they promise their voters.

In this case, Kilicdaroglu’s rhetoric is more radical than Erdogan’s. So radical that it could well be considered racist by the standards customary in Germany. Kilicdaroglu firmly rejects this accusation. He claims that the well-being of the Turks is important to him and denies being a racist.

The AKP justifies Erdogan’s attitude towards Putin, which is at times disturbing for NATO partners, with the well-being of its own people. Kilicdaroglu’s closeness to NATO is blamed on the rival as treason.

More radical towards the Greeks

Kilicdaroglu is also more extreme in his choice of words towards NATO partner Greece. While Erdogan likes to question the sovereignty of the Greek Aegean islands and threatens that “we could come one night”, Kilicdaroglu criticizes him for not following the martial words with deeds.

He sees himself in the tradition of his role model Bülent Ecevit, who risked war with Greece in 1974 and occupied a third of the island state of Cyprus. From Greece itself there is no official statement regarding a candidate’s preference.

In numerous interviews, Foreign Minister Nikos Dendias only hinted that there were open channels of communication even in the ice age of diplomatic relations between the two countries, and that Athens knew what Erdogan was up to. Kilicdaroglu is an unknown unknown in this respect.