In the past, when using health data, “a little too much attention was paid to the risks” and as a result “good concepts were implemented too slowly,” said the chairwoman of the German Ethics Council, Alena Buyx, at the Bioethics Forum event “patient-oriented data use”. At the same time, according to Buyx, “a lot of data from our everyday life is too relaxed”. She conceded, however, that data protection was wrongly scolded. The health data should be about “many individual benefits and the benefits for the common good”. Basic considerations on health data had the German Ethics Council 2017 in its statement “Big Data and Health – Data sovereignty as informational freedom design” (PDF) presented.

“Each patient has their own medical history,” says Ursula Klingmüller. She conducts research at the German Cancer Research Center. The health data can be used to calculate an individual risk for certain diseases.

health data usage

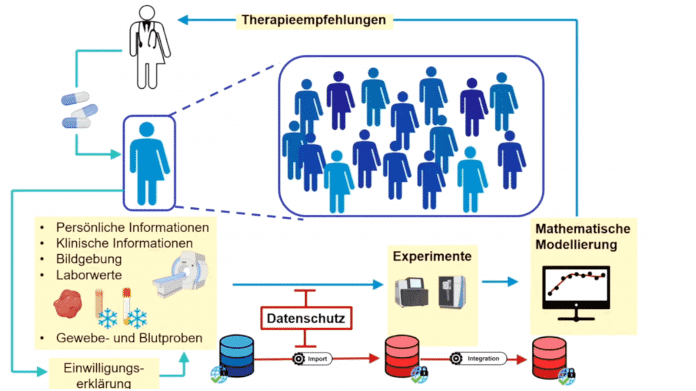

(Image: German Ethics Council)

The data is currently shared if the patient gives informed and informed consent – a research pseudonym is used for this. The data can then be used to generate mathematical models from which, for example, therapy recommendations can be developed. There are currently extensive regulations in Germany that “often greatly delay research projects” because complicated contracts have to be concluded over many years, such as joint controller agreements that regulate joint responsibility for the data. The fact that medical products are developed based on large data collections also means that there are also economic interests in the high-quality data collections.

risk of discrimination

The data poses a risk of discrimination and stigmatization. According to Klingmüller, in professional life or with insurance companies, these are completely justified concerns, for example because treatment options have been denied due to previous treatments. Particularly in the case of particularly sensitive data such as mental illnesses, one does not want them to appear in any files and possibly become accessible to third parties. In the case of a fatal illness, however, “survival and the preservation of quality of life” are in the foreground. These patients are usually willing to share their data and, according to Klingmüller, show solidarity by doing so. For these patients, an opt-out solution would be better. It is therefore important to discuss the possibility of automatic data transfer.

“Right to data portability” in the foreground

The European Health Data Space (EHDS) aims to improve patient data use at EU level, but at the same time control rights, says Anne Riechert, Professor of Data Protection Law and Information Processing. It therefore raises the question of the compatibility of these two objectives. The relevant regulations, such as the Data Governance Act or the draft eHealth Regulation (EHDS), are more about “promoting and expanding the right to data portability”. Consent is still classified by many as the most important tool, which is also justified. According to Riechert, one has to admit that practicality is not always the case.

In the area of data that is particularly worthy of protection, health data, there are of course increased requirements. “We have a strict data processing ban,” says Riechert. Consent to data processing is therefore expressly necessary. In addition, the processing must be purposeful. According to Riechert, it is often said that “we have a research privilege” and reference is made to broad consent – but the term broad consent is not found in the GDPR. After recital 33 While consent can be more flexible in the area of research, the description of the purpose cannot be dispensed with. Therefore, the European Data Protection Committee also points out that there is a procedure to increase the transparency of processing during the research project, for example to be able to give or withdraw consent more easily. According to Riechert, data protection standards, including declarations of consent, can lead to legal certainty and trust.

GDPR as an obstacle?

There are currently heated discussions about the voluntary nature of the electronic patient record (ePA). According to Riechert, the member states must always be able to regulate additional conditions and restrictions independently. When introducing the ePA, one has to reconsider in each individual case whether data processing is also necessary for individual health care. The Data Protection Board calls for objective necessity and a fact-based assessment of necessity.

Right of objection can be limited by law

According to Riechert, within the framework of the GDPR one could also say: “We use the electronic health record for public health interests”. However, this is a completely different purpose than what we have in individual healthcare. So far, the public health interest has not necessarily been reflected in the ePA. One has to ask oneself what the political goal is. As soon as there is a national law to allow research purposes, according to data protection officials, the rights of those affected can also be restricted, in principle, for example, the right of objection.