In September 2020, the Colombian publisher Alejandro Alba Garcia had the idea of exploring the Panamericana Editorial catalog in search of something that would unify the voices of certain writers who had been working on similar concepts and themes in their respective literatures, from their respective perspectives.

The search was not aesthetic. The editor did not intend to find any current of thought or take a position in relation to society or art itself; Alba’s intention, perhaps without knowing it, was focused on seeing how a person is capable of opening or closing a door, and not so much in the literal action, but in everything that the concept entails

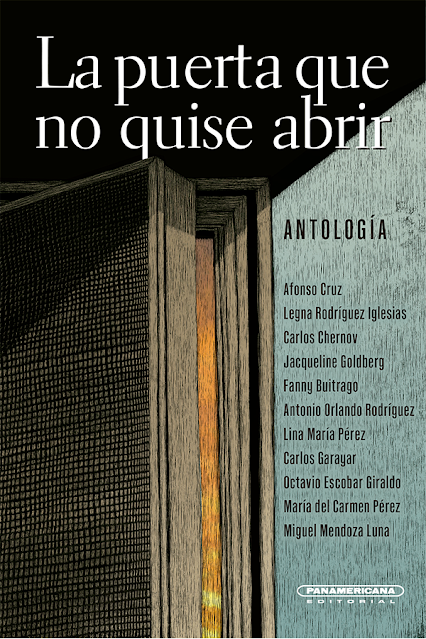

Eleven writers, eleven ways of writing about a door, that’s what the editor came to; eleven voices from different parts of Latin America and Europe who write about futurism and dystopia, and talk about deviant love and intersecting genres, who make essay and story at the same time and narrate life.

In “The door I didn’t want to open”authors of the stature of María del Carmen Pérez (Nicaragua), Legna Rodríguez Iglesias (Cuba), Jacqueline Goldberg (Venezuela), Carlos Chernov (Argentina), Antonio Orlando Rodríguez (Cuba), Afonso Cruz (Portugal), Carlos Garayar (Peru) and the Colombians, Fanny Buitrago, Lina María Pérez, Octavio Escobar and Miguel Mendoza congregate, in a mixture of styles and geographies.

Each story, all different one from the other, is accompanied by illustrations, sometimes bright, sometimes dark, by Andrés Rodríguez, in a reinterpretation of the story, reads the back cover of the book. Because “whoever opens the door, whoever sees beyond the surface of the door is wanting something else: he wants to flee.”

“There are few more precise and frequent metaphors to talk about reading a book than that of a door that opens to an unknown place. Two images facilitate this metaphor: the hinge mechanism (that page that turns) and the act of opening (that book that opens). There are endless variations on this same aria and often include, of course, the semantic and the erotic. In any case, the identification is suggestive: the possibility of access, the entrance to an unknown dimension is attractive and it is nothing other than the search that Baudelaire spoke of: going “to the bottom of the unknown, to find the new”. The much talked about pleasure of novelty is not foreign to that door (or to that book)” – (from the prologue by Alejandro Alba García).

It may interest you: Fanny Buitrago: The wonderful thing about being alive and dissatisfied

Readers will find in these pages a bit of all the good that comes from the work of each of these writers and will also be able to attend a true celebration of the short story genre.

Next, courtesy of Panamericana Editorial, we share a fragment of one of the stories included in “The door I didn’t want to open”:

It was not true that confinement or loneliness intimidated him or that bad news eroded his mettle or integrity. He had a firm heart and cinched pants.

In a way he was in good company. He had plenty of time to read, reflect, evaluate his previous life. As if it were a state-of-the-art computer, its memory typed, moved chips, opened windows and new files. He treated his arrogant self coldly without allowing him to harbor too many feelings or emotions.

oh! A memory focused on women, her women, whom he missed so much. Most of them were faceless and perhaps she had loved them when she was not old enough to do so. Women from his past and his difficult time, with faded faces and radiant smiles, all and none. Some without names and others without voices, blurred dream silhouettes on the walls and bars of the prison, transformed into bitter real life.

He, Rogelio Montero, was not even allowed to look out into the patios and had restricted visits. For months he had not listened to classical music or seen the light or the reflection of the moon. He, too, hadn’t enjoyed the limpid smell of rain.

Women for years and years forgotten who, suddenly, slipped into his room—which he refused to call a cell—and looked at him mockingly from the stairs of insomnia or the walls. Sometimes one by one, sometimes by two, light as flowers and withered petals; some with eyes glazed with compassion, others with mockery and disbelief. Girls from classrooms and schoolyards, by his side in auditoriums, dances, cafeterias, to whom he had promised love, tenderness, eternity, and unveiled passions.

She had bought boxes of chocolates and truffles for all of them, colognes, quartz and jade pendants and earrings, and natural silk scarves. Gifts that at that moment, when she most needed to extend a hand and remember happy gestures, none seemed to remember or appreciate. Gifts to whom? To the girls who go to clubs and concerts, the regulars at Parque de la 93, who wanted to attend the National Theater, the events at the Julio Mario Santo Domingo library, or those who were content with beaded bracelets and dreamed of traveling and working in USA.

They were importunate women, with no names to remember, oblivious to the memory of their skin, the demands of routine, and desire. What were they doing there? Perhaps for these reasons he had forgotten those faces to which tears were also added, darkened temples and foreheads, disappointments… Why did they annoy him with his ghostly aromas and scratches? Neither he nor his insomnia were interested in them… None of them! In his innocence she had believed she loved, needed, shared with a lady: his lady.

Day after day of visiting or not visiting, Sunday to Sunday, Monday and holidays (after the initial scandal had subsided, which was followed by scandals), he clung to the announcement and change of tone in the voice of the guard on duty, the visit of Ágata: “It’s about his wife.”

In addition to suffering the wait, the waits, she needed his love and understanding as much as possible, the softness and tact that adorned his treatment and personality, the sparkle in his eyes, his passion in bed, the tone of his voice.

What happened to his wife?

When the scandal subsided, Ágata Loreto left Bogotá without giving him any explanations. However, she told the journalists and anyone who wanted to listen that she knew nothing about her husband’s affairs; she nothing she wanted to know. With his attitude he blamed him and more blame, as if his father and his brothers were people of immaculate deeds, and not responsible for the pulse and rudder, not those who flattered and pushed Rogelio to intervene in a series of deals and compromises that led him to to jail. He was not on his way to wealth and prosperity, nor to live like a king in a condominium in Cartagena, Kavala, Marbella or the French Riviera, as he was promised.

So it was not given to expect affection, less the loving understanding of a conjugal visit. In such circumstances, Ágata was not interested in being her wife or mistress. He was not willing to file complaints either, he had enough with the claims of his sisters, the paperwork from the lawyers. All those who called themselves his best friends claimed apologies, suspicions, reasons for leaving, he wouldn’t see their hair.

As for the situation, he himself had caused it. The horrendous Siberian prisons described by novelists like Dostoyevsky and Solzhenitsyn were beside the point, even though a joker with a false name and sender had sent him a second-rate book, published back in the 1960s, Prison, award-winning, thumbed up and underlined. . He couldn’t complain about the treatment or the food they brought him from restaurants, or the clothes his sisters sent him washed and ironed. They were resentful, they followed the example of Ágata.

Ágata was his soul mate, as they said in the movies; hurt, frightened, she denied him her presence. Ágata, the chosen wife almost in a crowd, would have disappeared from her life and her desires with ease but for marriage. Ágata, a hard-fought commitment, well organized, one of her greatest successes. He liked it and it was convenient, it was her goal towards the summit, a relationship eventually transformed into affection.

Keep reading:

The paths traveled by the Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez

From Parque Santander to the Corferias site: 35 years of the Bogotá International Book Fair