125 years ago he created one of the first and longest-lasting comic strips in the western world. His slapstick picture stories attracted a mass audience and at times were published in hundreds of newspapers in the United States. A German comic prize has even been named after him for several years.

Nevertheless, the life and work of the German-American comic pioneer Rudolph Dirks and his long-running series “The Katzenjammer Kids” have only been researched and documented to a limited extent in recent decades.

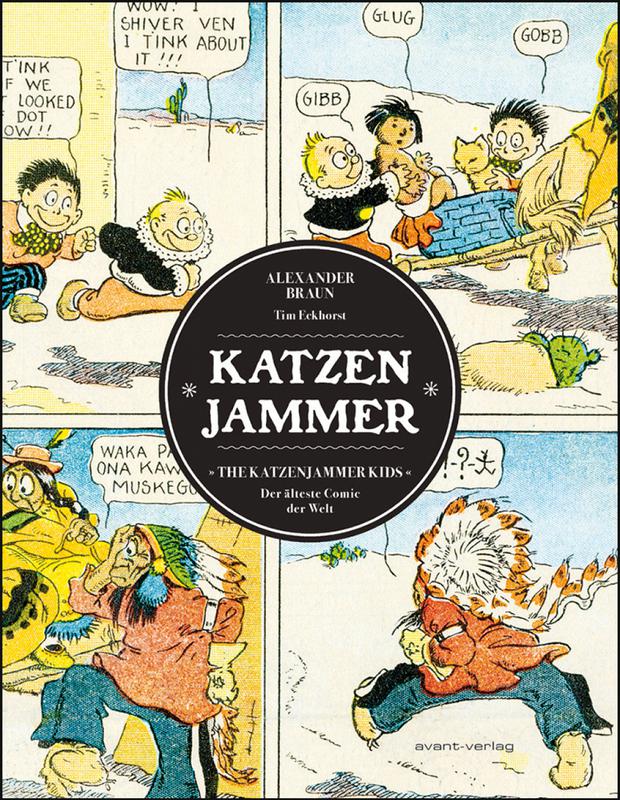

The art historians Alexander Braun and Tim Eckhorst have been working on closing this gap for several years. Now their efforts with an exhibition (until April 10th in the Dortmund showroom) and an opulent catalog entitled “Katzenjammer: The Katzenjammer Kids – The oldest comic in the world” (avant, 472 p., 59 €) reached its current peak.

Hans and Fritz instead of Max and Moritz

“Something with children” was what the editors of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal wanted. It was the year 1897 and the young draftsman Rudolph Dirks, who had just published his first cartoons and was confronted with this wish, thought of something he knew from his old homeland: the picture stories by Wilhelm Busch.

This is what the Schleswig-Holstein native later said, who emigrated to the USA with his parents and siblings at the age of seven.

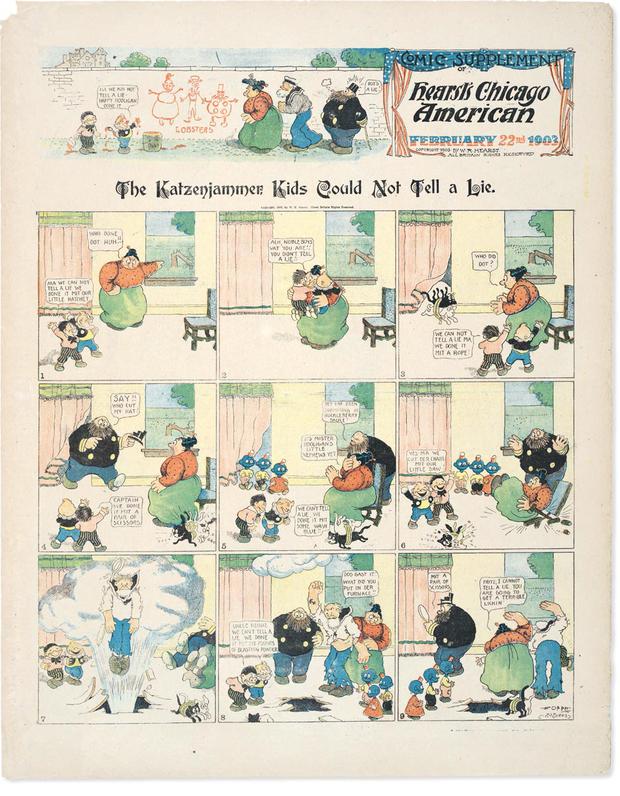

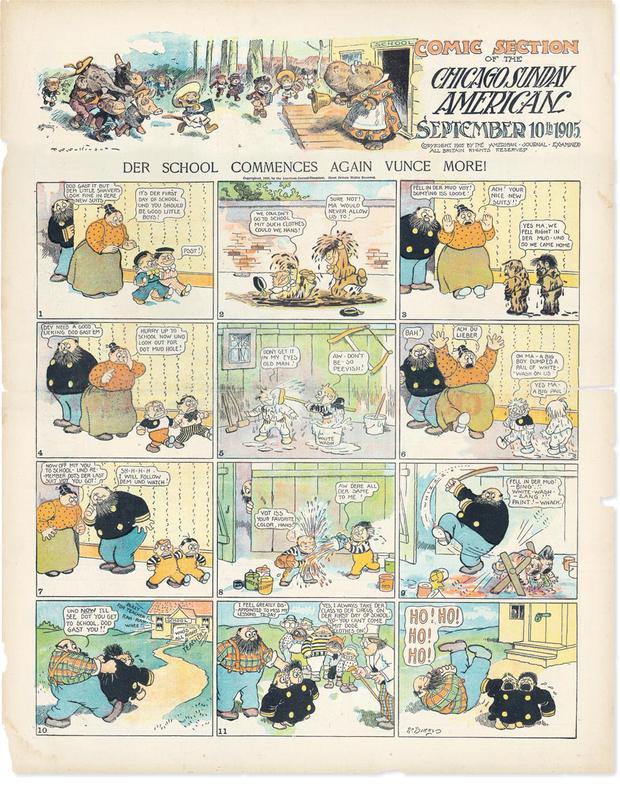

And what then appeared in the “New York Journal” on December 12, 1897 initially looked to a large extent like a copy of the well-known rascal stories from Germany. Except that the bullies, whose wild pranks are told picture by picture, are not called Max and Moritz, but Katzenjammer Kids, as can be read in the title of the otherwise initially wordless sequences.

Later, the Radau brothers were also given first names, Hans and Fritz, which identified them as German immigrants, as did the German-English gibberish that was to become their trademark.

“Decades of disregard for comics”

Little by little, the near-plagiarism was to become something completely independent with an extensive cast of characters and diverse adventure stories that paved the way for the modern comic strip.

Their joint work is the result of years of partly detective work, because the material situation is particularly poor in this case. This is cited in the foreword as one of the reasons why there has not yet been a comprehensive appreciation of Dirks’ creation, which has been expanded and continued by other artists over the years.

Hardly any original drawings by Dirks and other artists involved in the “Katzenjammer Kids” have survived, and newspaper pages and other historical documents have apparently only survived the decades to a very limited extent.

The authors attribute this primarily to the “cultural approach to the medium of comics in general”, as they lament: “The decades-long disregard for comics – a medium that had an audience counted in millions – the destruction of original drawings and documents, not questioning the artists while they were alive, all of this leaves behind a patchwork quilt that still raises almost as many questions as it provides answers.”

Comics for millions

It is all the more remarkable how much material was brought together for this monograph and brought into a coherent narrative that ranges from the beginnings of Dirks’ family history through the remarkably turbulent publication history of the “Katzenjammer Kids” to the discontinuation of the series in 2006.

Some of it could already be read in 2018 in the anthology “Rudolph Dirks – Zwei Lausbuben und diefindung des Modernes Comics”, which was published on the occasion of an exhibition in Rudolph Dirks’ northern German place of origin Heide and in which the two authors were involved.

For the new monograph, however, they delved much deeper into the subject, evaluated further material and processed it into a work that is particularly impressive visually.

Hundreds of high-quality reproductions of newspaper pages, photos, drawings and other documents on the large-format pages invite you on a journey through the decades and often convey very clearly, without many words, what made the early comic strips, especially those of the first decades of the 20th century, and why this art form came about thrilled an audience of millions at the time – long before radio and cinema and later television and the Internet competed with newspapers and comics as mass media and the “Katzenjammer Kids” lost their importance.

Life stories in first person form

However, in contrast to its topic, access to this monograph is anything but easy. Anyone who previously knew little or nothing about the “Katzenjammer Kids”, their illustrators and those involved in their publication must be patient when reading. Because Braun and Eckhorst take a lot of time to fan out the biographies of Rudolph Dirks and his contemporaries and to classify their works in terms of cultural history.

Only slowly does it become clear what connects them all and who played which role in this story. A summary would have been helpful at the beginning, giving an overview of the topic.

To make matters worse, the authors have chosen a style that is not always helpful for their explicitly documentary concerns. In addition to extensive biographical facts and information on the political, economic and social context of the comic strips, they have enriched most of the life stories of the characters with semi-fictional passages in which the actors talk about their lives in first-person form. This has almost literary quality in some places, but is rather problematic overall.

It is usually difficult to understand what is fact and what is fiction and where the authors get their knowledge of the supposed thoughts of their actors. This is especially irritating in the case of Rudolph Dirks’ younger brother Gus, who worked for a time on Katzenjammer Kids. Gus Dirks was an enormously talented artist who had created his own successful comic strip in Bugville, populated by anthropomorphic animal characters. In the summer of 1902, at the age of 21, he committed suicide.

In the chapter dedicated to him, Braun and Eckhorst have the dead man ponder in a long monologue how this came about and whether this step made sense. That seems inappropriate, especially at this point, especially since the biographical facts researched by the authors and stories passed down in the family would have been enough to paint a vivid picture of Gus Dirks.

Despite these limitations, this monograph is another milestone in German-language comic historiography, which Braun in particular has advanced in recent years with exhibitions and catalogs on the pioneers of the art form such as Will Eisner and Winsor McKay, as well as subject areas such as western and horror comics .

To home page