NY- Deshawn Hendricks, 26, wants to check his medications for the powerful opioid fentanyl whenever he can because, as a crack user, he’s worried it could cause a life-threatening overdose.

Matthew Todd, 32, is getting tested for another reason: As an opioid user, he has come to depend on the fast, intense high that fentanyl provides and wants to make sure what he bought is “real.”

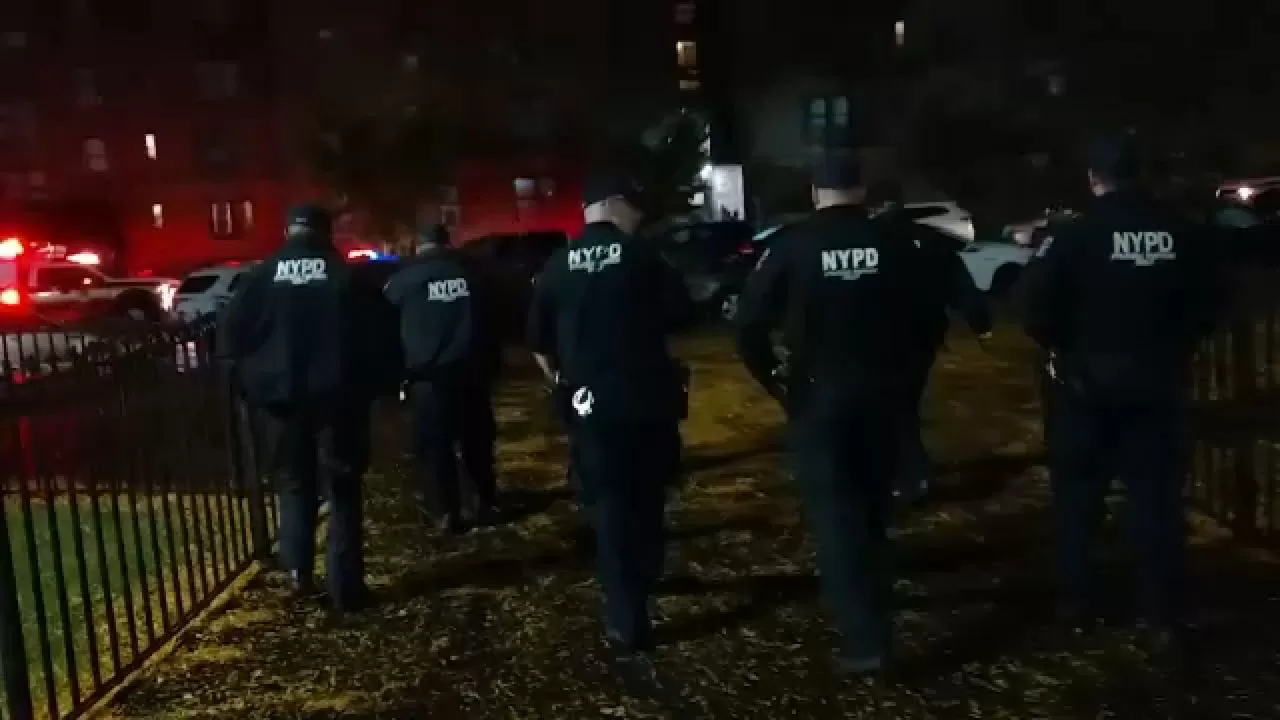

On a sidewalk running under the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, both men accepted fentanyl test strips from community workers, along with sandwiches, water and Narcan, a nasal spray that reverses overdose. Around him, some people were openly injecting drugs.

Hendricks, who has a 1-year-old daughter, said she suspected fentanyl was added to her crack to make the drug more addictive and harder to quit. Using a test strip, she said, “gives me the peace of mind to explain what I’ve been feeling.”

As the nation grapples with a deadly overdose crisis, fueled largely by illicit fentanyl, a consensus is developing, from President Joe Biden’s White House to political leaders in conservative states like Texas, Georgia and Alabama, that Widespread distribution of fentanyl test strips may be an effective, albeit limited, means of reducing the destructive impact of the drug.

Over the past year and a half, 16 additional states have passed laws legalizing the strips. Mississippi, Ohio and South Dakota have joined 20 other states, including New York, where stripping was already legal. And bills to legalize them are pending in almost every other state, where they are still banned as they are considered drug paraphernalia.

The strips, which retail for about a dollar, are emerging as common ground in a bitter debate over the overdose epidemic, with one side prioritizing law enforcement as a way to prevent use. of drugs, and the other emphasizes safer use and treatment.

“There’s a sense that fentanyl has really changed the game,” said Corey Davis, director of the Harm Reduction Legal Project Online for Public Health Law, which tracks state drug testing laws.

“There’s not a lot of specific things you can do to combat it.”

More than 2,100 people died from an accidental fentanyl overdose in 2021 in New York City, among more than 67,000 deaths nationwide.

But the strips serve a different function depending on the user.

Fentanyl is now present in much of the illicit drug supply, in unpredictable amounts. For people who use pills, ketamine, cocaine, or MDMA, for example, fentanyl strips can be particularly important because people with no opioid tolerance are at higher risk of fentanyl overdose.

Other users, including many former heroin users, have become dependent on fentanyl, and a positive result is unlikely to prevent them from using. But it can act as a reminder to use more cautiously.

“The whole thing is, know your drug,” said José Martínez, who participates in street outreach with the National Coalition for Harm Reduction in the Bronx.

For people now looking for fentanyl, a new type of strip may be more useful: one that tests for xylazine, a veterinary tranquilizer that can cause hideous skin wounds. Known on the street as tranq, xylazine increases the level of fentanyl and is already in more than 90 percent of the fentanyl supply in Philadelphia. It has also begun to appear in New York and elsewhere.

access

Sales of fentanyl test strips have skyrocketed since the start of the pandemic as knowledge about them has increased, said Iqbal Sunderani, chief executive of BTNX, a Canadian company that created the xylazine test strips and is also the leading manufacturer of fentanyl strips.

The company sold 8 million tests in 2022, up from about 1.5 million in 2020, almost all to harm reduction organizations. A flood of Chinese-made strips is also entering the market.

Opioid users “are very interested in having them, even though there is fentanyl in the entire heroin supply,” said Dr. Andrea Littleton of BronxWorks, the group that handed out strips in the Bronx underpass.

“But I think actually seeing the test come back positive changes their behavior — they’re still going to use it, but usually they’ll do a batch test, or make sure someone checks them out,” he added.

Still, the strips can be hard to find for many New Yorkers.

Darryl Phillips, 48, is a movie producer and test strip evangelist trying to change that reality. He is the executive director of the Always Strive and Prosper (ASAP) foundation. It was founded in honor of his friend A$AP Yams, born Steven Rodriguez, a hip-hop influencer who died of an accidental overdose in 2015.

In some 60 bars, restaurants and galleries around the city, there is now a small transparent box marked with the ASAP logo behind the bar or on a table.

The boxes contain dozens of fentanyl test kits, and Phillips and his group of volunteers update them regularly. Each kit contains a test strip, a vial of clean water, a small tin container to dissolve a sample of the drug, and an easy-to-follow instruction card designed by him.

The city government also distributes test strips; it gave out 48,000 in 2022, most of them through nonprofit organizations that target chronic opioid drug users.